Get the Latest in Your Inbox

Want to stay up to date on the state of the world’s forests? Subscribe to our mailing list.

Subscribe

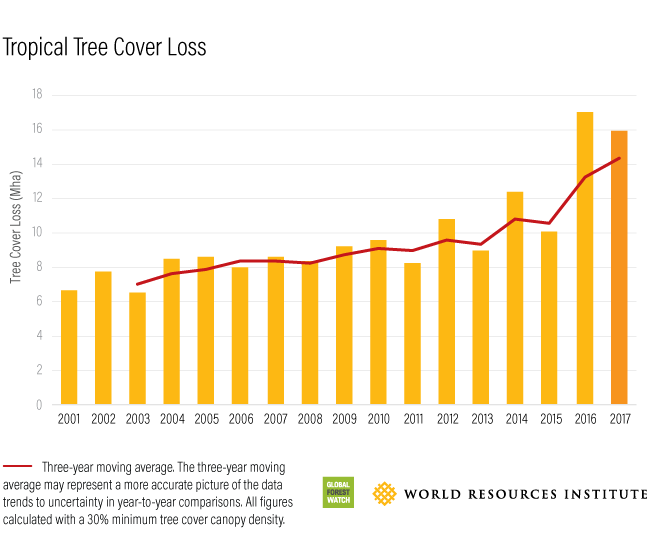

The 2017 tree cover loss numbers are in, and they’re not looking good. Despite a decade of intensifying efforts to slow tropical deforestation, last year was the second-highest on record for tree cover loss, down just slightly from 2016. The tropics lost an area of forest the size of Vietnam in just the last two years.

In addition to harming biodiversity and infringing on the rights and livelihoods of local communities, forest destruction at this scale is a catastrophe for the global climate. New science shows that forests are even more important than we thought in curbing climate change. In addition to capturing and storing carbon, forests affect wind speed, rainfall patterns and atmospheric chemistry. In short, deforestation is making the world a hotter, drier place.

In light of these high stakes, those of us in “Forestry World” who dedicate our professional lives and personal passions to saving the rainforest need to pause and reflect: If the indicators are going in the wrong direction, are we doing something wrong?

Brick on the Accelerator, Feather on the Brake

There’s no mystery on the main reason why tropical forests are disappearing. Despite the commitments of hundreds of companies to get deforestation out of their supply chains by 2020, vast areas continue to be cleared for soy, beef, palm oil and other commodities. In the cases of soy and palm oil, global demand is artificially inflated by policies that incentivize using food as a feedstock for biofuels. And irresponsible logging continues to set forests on a path that leads to conversion to other land uses by opening up road access and increasing vulnerability to fires.

A large portion of that logging and forest conversion is illegal, according to the laws and regulations of producer countries, yet illegality and corruption remain endemic in many forest-rich countries. And Indigenous Peoples—whose presence is associated with maintaining forest cover, yet whose land rights are often unrecognized—continue to be murdered when they attempt to protect their forests.

The situation reminds me of the many movies that feature a runaway train: The throttle of global demand for commodities has been engaged, and the brakes of law enforcement and indigenous stewardship have been disabled. The only way to prevent a disastrous train wreck is for the hero (or heroine) to get into the conductor’s seat, remove the brick on the accelerator, and hit the emergency brakes.

We actually know how to do this. We have a large body of evidence that shows what works. Brazil, for example, reduced large-scale deforestation in the Amazon by 80 percent from 2004-2012 by increasing law enforcement, expanding protected areas, recognizing indigenous territories, and applying a suite of carrots and sticks to reign in uncontrolled conversion to agriculture, even while increasing production of cattle and soy. The problem is that our current efforts to apply these tools amount to a feather on the brake compared to the brick on the accelerator.

Forests Are Collateral Damage in Major Economic and Political Events

To a certain extent, the bad news in the 2017 tree cover loss numbers reflects collateral damage from unrelated political and economic developments in forested countries. Colombia’s 46 percent increase in tree cover loss is likely linked to its recent conflict resolution, which opened up to development large areas of forest previously controlled by armed rebel forces. While the doubling of Brazil’s tree cover loss from 2015 to 2017 was in part due to unprecedented forest fires in the Amazon, the uptick is likely also attributable to a relaxation of law enforcement efforts in the midst of the country’s ongoing political turmoil and fiscal crisis. Indeed, it is striking how many of the world’s tropical forested countries have either experienced a recent change in government (Liberia, Peru), are currently in political crises (Brazil, Democratic Republic of Congo), are in the midst of elections (Colombia), or will face elections in the near future (Indonesia).

We Know the Solutions for Stopping Deforestation

This context hammers home what we already knew: No amount of international concern about tropical forests will make a difference unless it meaningfully connects to domestic constituencies in forested countries, and changes the incentives that drive deforestation.

One of the key strategies for aligning national priorities with anti-deforestation actions started a decade ago. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation and enhancing forest carbon stocks, or REDD+, is a framework endorsed by the Paris Agreement on climate change that encourages rich countries to pay developing countries for limiting deforestation and forest degradation. Unfortunately, the volume of REDD+ funding on offer (about a billion dollars per year) remains trivial compared to the $777 billion provided since 2010 for financing agriculture and other land sector investments that put forests at risk. This is surely one reason why domestic coalitions for change in countries participating in REDD+ have been unable to overcome competing coalitions for deforestation-as-usual.

While the prospects for immediate increases in REDD+ finance remain bleak, other strategies to strengthen domestic constituencies for reform show promise.

Brazil pioneered a system of monitoring deforestation by satellite. The public disclosure of that data was key to generating political will and the information necessary for fighting illegal clearing. Now, remote-sensing tools are helping communities and law enforcement officials around the world to detect and respond to illegal deforestation in near-real time. For example, Peru’s Ministry of Environment distributes weekly deforestation alerts to more than 800 government agencies, companies and civil society groups, which led to several prosecutions in 2017.

International cooperation on law enforcement can also create domestic incentives for forestry sector reform. In late 2016, Indonesia became the first country to receive a license to export to the European Union timber verified as legally harvested. By ensuring that its timber was harvested legally, Indonesia secured access for its forest products in a lucrative international market.

Indonesia has also witnessed the application of a new generation of transparency tools to fight deforestation. For example, in 2017, civil society groups used publicly available databases on corporate finance and governance to uncover monopolistic practices and non-compliance with plantation regulations among 15 companies in the palm oil sector. They then shared their findings with Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission and other government authorities in a position to respond with policy or legal action.

Finally, there’s increased action at the sub-national level. Dozens of governors and district heads in forest-rich jurisdictions around the world have committed to low-emissions development. For example, the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso launched a “Produce, Conserve, and Include” strategy to end illegal deforestation while promoting sustainable agriculture. Some of the companies that have made anti-deforestation commitments are considering preferential sourcing of commodities from such jurisdictions as a way of both reducing risk and encouraging continued progress toward better land-use management.

Those of Us in “Forestry World” Can’t Do It Alone

There are clearly solutions out there, but they need to be scaled up and expanded to forests throughout the world. This week, more than 500 citizens of Forestry World are gathering at the Oslo Tropical Forests Forum to reflect on the last 10 years of efforts to protect forests, and chart a way forward. But we can’t do it alone.

Preliminary analysis suggests that a significant chunk of forest loss in 2017 was due to “natural” disasters of the sort expected to become more frequent and severe with climate change. Hurricane Maria flattened forests in the Caribbean, and fires burned large areas of Brazil and Indonesia over the last few years. While degradation of forests through logging and fragmentation by roads renders them less resilient to extreme weather events, there is a limit to which forest-specific interventions can be effective in the face of a changing climate. While stabilizing the global climate is contingent on saving the world’s forests, saving the forests is also contingent on stabilizing the global climate.

In addition to doubling down on the proven strategies for reducing deforestation (and allocating a fair share of climate finance toward those efforts), all countries need to up their game on climate action.

Nature is telling us this is urgent. We know what to do. Now we just have to do it.

{"Glossary":{"141":{"name":"agroforestry","description":"A diversified set of agricultural or agropastoral production systems that integrate trees in the agricultural landscape.\r\n"},"101":{"name":"albedo","description":"The ability of surfaces to reflect sunlight.\u0026nbsp;Light-colored surfaces return a large part of the sunrays back to the atmosphere (high albedo). Dark surfaces absorb the rays from the sun (low albedo).\r\n"},"94":{"name":"biodiversity intactness","description":"The proportion and abundance of a location\u0027s original forest community (number of species and individuals) that remain.\u0026nbsp;\r\n"},"95":{"name":"biodiversity significance","description":"The importance of an area for the persistence of forest-dependent species based on range rarity.\r\n"},"142":{"name":"boundary plantings","description":"Trees planted along boundaries or property lines to mark them well.\r\n"},"98":{"name":"carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e)","description":"Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) is a measure used to aggregate emissions from various greenhouse gases (GHGs) on the basis of their 100-year global warming potentials by equating non-CO2 GHGs to the equivalent amount of CO2.\r\n"},"153":{"name":"climate domain","description":"Major ecosystem regions, summarized as boreal, temperate, tropical and subtropical.\u0026nbsp;"},"99":{"name":"CO2e","description":"Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) is a measure used to aggregate emissions from various greenhouse gases (GHGs) on the basis of their 100-year global warming potentials by equating non-CO2 GHGs to the equivalent amount of CO2.\r\n"},"1":{"name":"deforestation","description":"The change from forest to another land cover or land use, such as forest to plantation or forest to urban area.\r\n"},"77":{"name":"deforested","description":"The change from forest to another land cover or land use, such as forest to plantation or forest to urban area.\r\n"},"76":{"name":"degradation","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes.\r\n"},"75":{"name":"degraded","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes.\r\n"},"79":{"name":"disturbances","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"68":{"name":"disturbed","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"65":{"name":"driver of tree cover loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"70":{"name":"drivers of loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"81":{"name":"drivers of tree cover loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"102":{"name":"evapotranspiration","description":"When solar energy hitting a forest converts liquid water into water vapor (carrying energy as latent heat) through evaporation and transpiration.\r\n"},"154":{"name":"fastwood monoculture","description":"Stands of single species planted trees that grow quickly.\u0026nbsp;"},"53":{"name":"forest degradation","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s quality and ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes."},"54":{"name":"forest disturbance","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"100":{"name":"forest disturbances","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"5":{"name":"forest fragmentation","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"155":{"name":"Forest Landscape Restoration","description":"The ongoing process of restoring landscapes to regain ecological functionality and enhance human well-being across deforested or degraded forest landscapes."},"156":{"name":"forest moratorium","description":"A temporary restriction on activities that cause forest loss or degradation."},"69":{"name":"fragmentation","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"80":{"name":"fragmented","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"74":{"name":"gain","description":"The establishment of tree canopy in an area that previously had no tree cover. Tree cover gain may indicate a number of potential activities, including natural forest growth or the crop rotation cycle of tree plantations.\r\n"},"143":{"name":"global land squeeze","description":"Pressure on finite land resources to produce food, feed and fuel for a growing human population while also sustaining biodiversity and providing ecosystem services.\r\n"},"7":{"name":"hectare","description":"One hectare equals 100 square meters, 2.47 acres, or 0.01 square kilometers.\r\n"},"66":{"name":"hectares","description":"One hectare equals 100 square meters, 2.47 acres, or 0.01 square kilometers."},"67":{"name":"intact","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"78":{"name":"intact forest","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"8":{"name":"intact forests","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"55":{"name":"land and environmental defenders","description":"People who peacefully promote and protect rights related to land and\/or the environment.\r\n"},"161":{"name":"logging concession","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"157":{"name":"logging concessions","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"160":{"name":"Logging concessions","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"9":{"name":"loss driver","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation).\r\n"},"10":{"name":"low tree canopy density","description":"Less than 30 percent tree canopy density.\r\n"},"104":{"name":"managed natural forests","description":"Naturally regenerated forests with signs of management, including logging and clear cuts.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"91":{"name":"megacities","description":"A city with more than 10 million people.\r\n"},"57":{"name":"megacity","description":"A city with more than 10 million people."},"86":{"name":"natural","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions).\u0026nbsp;"},"12":{"name":"natural forest","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions). \r\n"},"63":{"name":"natural forests","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions).\u0026nbsp;"},"144":{"name":"open canopy systems","description":"Individual tree crowns that do not overlap to form a continuous canopy layer.\r\n"},"88":{"name":"planted","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"14":{"name":"planted forest","description":"Planted trees \u2014 other than tree crops \u2014 grown for wood and wood fiber production or for ecosystem protection against wind and\/or soil erosion.\r\n"},"73":{"name":"planted forests","description":"Planted trees \u2014 other than tree crops \u2014 grown for wood and wood fiber production or for ecosystem protection against wind and\/or soil erosion."},"148":{"name":"planted trees","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"149":{"name":"Planted trees","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"15":{"name":"primary forest","description":"Old-growth forests that are typically high in carbon stock and rich in biodiversity. The GFR uses a humid tropical primary rainforest data set, representing forests in the humid tropics that have not been cleared in recent years.\r\n"},"64":{"name":"primary forests","description":"Old-growth forests that are typically high in carbon stock and rich in biodiversity. The GFR uses a humid tropical primary rainforest data set, representing forests in the humid tropics that have not been cleared in recent years.\r\n"},"58":{"name":"production forest","description":"A forest where the primary management objective is to produce timber, pulp, fuelwood, and\/or nonwood forest products."},"89":{"name":"production forests","description":"A forest where the primary management objective is to produce timber, pulp, fuelwood, and\/or nonwood forest products.\r\n"},"159":{"name":"restoration","description":"Interventions that aim to improve ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in degraded landscapes. Landscapes may be forested or non-forested."},"87":{"name":"seminatural","description":"Forest with predominantly native trees that have not been planted. Trees are established through silvicultural practices, including natural regeneration or selective thinning.FAO"},"59":{"name":"seminatural forests","description":"Forest with predominantly native trees that have not been planted. Trees are established through silvicultural practices, including natural regeneration or selective thinning.FAO"},"96":{"name":"shifting agriculture","description":"Agricultural practices where forests are cleared, used for agricultural production for a few years, and then temporarily abandoned to allow trees to regrow and soil to recover.\u0026nbsp;"},"103":{"name":"surface roughness","description":"Surface roughness of forests creates\u0026nbsp;turbulence that slows near-surface winds and cools the land as it lifts heat from low-albedo leaves and moisture from evapotranspiration high into the atmosphere and slows otherwise-drying winds. \r\n"},"17":{"name":"tree cover","description":"All vegetation greater than five meters in height and may take the form of natural forests or plantations across a range of canopy densities. Unless otherwise specified, the GFR uses greater than 30 percent tree canopy density for calculations.\r\n"},"71":{"name":"tree cover canopy density is low","description":"The percent of ground area covered by the leafy tops of trees. tree cover: All vegetation greater than five meters in height and may take the form of natural forests or plantations across a range of canopy densities. Unless otherwise specified, the GFR uses greater than 30 percent tree canopy density for calculations.\u0026nbsp;\u0026nbsp;"},"60":{"name":"tree cover gain","description":"The establishment of tree canopy in an area that previously had no tree cover. Tree cover gain may indicate a number of potential activities, including natural forest growth or the crop rotation cycle of tree plantations.\u0026nbsp;As such, tree cover gain does not equate to restoration.\r\n"},"18":{"name":"tree cover loss","description":"The removal or mortality of tree cover, which can be due to a variety of factors, including mechanical harvesting, fire, disease, or storm damage. As such, loss does not equate to deforestation.\r\n"},"163":{"name":"tree cover loss due to fire","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"164":{"name":"tree cover loss due to fires","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"162":{"name":"tree cover loss from fires","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"150":{"name":"tree crops","description":"Stand of perennial trees that produce agricultural products, such as rubber, oil palm, coffee, coconut, cocoa and orchards."},"85":{"name":"trees outside forests","description":"Trees found in urban areas, alongside roads, or within agricultural land\u0026nbsp;are often referred to as Trees Outside Forests (TOF).\u202f\r\n"},"151":{"name":"unmanaged","description":"A forest that grows without human intervention and has no signs of management, including primary forest.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"105":{"name":"unmanaged natural forests","description":"A forest that grows without human intervention and has no signs of management, including primary forest.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"158":{"name":"tree cover loss from fire","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"}}}