Get the Latest in Your Inbox

Want to stay up to date on the state of the world’s forests? Subscribe to our mailing list.

Subscribe

The tropics lost a record-shattering 6.7 million hectares of primary rainforest in 2024, an area nearly the size of Panama. Driven largely by massive fires, that’s more than any other year in at least the last two decades.

According to new data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD lab and available on WRI’s Global Forest Watch platform, tropical primary forest disappeared at a rate of 18 football (soccer) fields per minute in 2024 — nearly double that of 2023. These are some of the most important forest ecosystems, critical for livelihoods, carbon storage, water provision, biodiversity and more. Their loss in 2024 alone caused 3.1 gigatonnes (Gt) of greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to slightly more than the annual CO2 emissions from India’s fossil fuel use.

Tropical primary forest loss increased 80% from 2023 to 2024

More

Fires burned 5 times more tropical primary forest in 2024 than in 2023. While fires are naturally occurring in some ecosystems, in tropical forests they are almost entirely human-caused, often started to clear land for agriculture and spreading out of control in nearby forests. 2024 was the hottest year on record, with hot, dry conditions largely caused by climate change and El Niño leading to larger and more widespread fires. Latin America was particularly hard hit, reversing the reduction in primary forest loss seen in Brazil and Colombia in 2023.

Although forests can recover following fires, the combined effects of climate change and conversion of forests to other land uses like agriculture can make this recovery more difficult and increase the risk of future fires.

Primary forest loss unrelated to fires also increased by 14% between 2023 and 2024, mostly driven by conversion of forests to agriculture. Over the last 24 years, forest clearing for permanent agriculture has been the largest driver of tropical primary forest loss, but in 2024 wildfire became the larger driver, responsible for almost half of the loss.

Wildfires were the biggest driver of tropical primary forest loss in 2024

More

And loss wasn’t contained to the tropics: Tree cover loss globally also reached a record high, with boreal regions like Canada and Russia experiencing extreme fires.

More

Why Do We Largely Focus on Tropical Primary Forests?

Though the tree cover loss data from the University of Maryland has global coverage, Global Forest Watch primarily focuses on loss in the tropics because that is where 94% of deforestation, or human-caused, long-term removal of forest occurs. This piece largely focuses on primary forests in the humid tropics, which are areas of mature rainforest that are especially important for biodiversity, carbon storage and regulating regional and local climate.

More

While there were some bright spots in 2024 — Indonesia and Malaysia both experienced less primary forest loss than in 2023 and their rates of loss are well below what they were a decade ago — the overall trend is heading in the wrong direction. Leaders of over 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders Declaration in 2021, promising to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. But we are alarmingly off track to meet this commitment: Of the 20 countries with the largest area of primary forest, 17 have higher primary forest loss today than when the agreement was signed.

The top 10 countries for tropical primary forest loss shifted from 2023 to 2024, with Bolivia rising to second

More

Clearly, more needs to be done to safeguard the world’s forests for the sake of people, nature and the climate. Here’s a deeper look at some of the major forest loss trends in 2024:

More

Primary Forest Loss Spiked in the Brazilian Amazon Due to Fires

Brazil saw a major increase in primary forest loss in 2024, largely driven by one of the worst fire seasons on record.

Brazil primary forest loss spiked in 2024, largely due to fire

More

Last year, Brazil experienced its most intense and widespread drought in seven decades, which —combined with high temperatures — caused fires to spread at an unprecedented scale throughout the country.

Other than fire, primary forest loss was mostly caused by clearing forests for soy and cattle farming.

Brazil has more tropical primary forest than any other country in the world and remains the largest contributor to forest loss, accounting for 42% of all primary rainforest loss across the tropics. Rates of non-fire related loss also increased by 13% in 2024 compared to 2023, but were still below peaks in the early 2000s and during President Jair Bolsonaro’s term. (Read about how the data from UMD compares to Brazil’s official deforestation monitoring system.)

Trends varied across different biomes:

Select Brazil biomes were affected by fire in 2024 with the Amazon reaching a post-2016 high

More

- The Amazon biome experienced the most loss since a record high in 2016, jumping 110% from 2023 to 2024. 60% of it was due to fires. Agricultural expansion is a major driver, with the vast majority of recent deforestation found to be illegal.

- The Pantanal, Brazil’s tropical wetland, had the highest percent of tree cover loss of any biome, losing 1.6% of its tree cover (more than double the 0.83% rate for all of Brazil). 57% was due to fires. Research shows that fires in the Pantanal are now 40% more intense than they would have been without climate change.

- Tree cover loss declined in other biomes, with the exception of the Atlantic forest. In the savannas of the Brazilian Cerrado, all tree cover loss decreased by 14% from 2023 to 2024, although this is within normal annual fluctuations.

While primary forest loss reached low levels in 2023 as newly elected President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva introduced pro-environmental policies — including revoking anti-environmental measures, recognizing new Indigenous territories and bolstering law enforcement efforts — this progress is threatened by the expansion of agriculture. At the state level, both Mato Grosso and Rondônia have proposed or approved legislation to weaken historic moratoriums designed to reduce deforestation. These laws could have knock-on effects since deforestation itself induces changes to rainfall that could reduce crop yields, requiring even more agricultural land.

Conservation policies and enforcement are critical, as well as more investment in national fire-prevention programs like Prevfogo, which trains local communities to respond to fire and practice fire-free sustainable land management.

More

Fires Devastate Bolivian Forests

Bolivia saw a whopping 200% increase in primary forest loss in 2024, following a record-breaking year for tree cover loss in 2023.

Bolivia primary forest loss saw an unprecedented increase in 2024

More

For the first time since our record-keeping began, Bolivia ranked second behind only Brazil in tropical primary forest loss, surpassing the Democratic Republic of the Congo despite having just 40% of its forest area.

Hot spots of primary forest loss in Bolivia 2002-2024 show the expansion of forest loss fronts across the country

More

Most fires in the country’s rainforests are started to clear land for industrial-scale farming, especially for cattle ranching (thought to be responsible for 57% of deforestation in Bolivia) and monoculture crops such as soy, sugarcane, corn and sorghum. While fire can be a traditional land management tool, increasingly hot and dry conditions have turned many of these burns into runaway fires, resulting in longer, more destructive fire seasons.

Bolivia experienced one of the most severe droughts on record in 2024; government statistics show that almost 12% of the country burned, including large areas of forest. Without early warning systems or adequate firefighting resources, rural communities experienced the worst of the flames, while urban residents suffered from wildfire smoke.

Government policies that deprioritize fire prevention and response and instead support the expansion of agribusiness also contributed to the blazes. In early 2024, the government lifted export quotas on soy and beef, boosting incentives for agricultural expansion. And agricultural development is not expected to slow: Following the 2024 fire season, the government eliminated all import taxes on agrochemicals and machinery and introduced a two- to five-year loan moratorium for individuals and companies affected by forest fires.

There was one bright spot: Charagua Iyambae, a newly established Indigenous Territory in southern Bolivia, managed to keep the fires at bay. Their investments in early warning systems and enforcement of land use-policies helped prevent the spread of forest fires for the second year in a row — a remarkable feat.

Bolivia’s Charagua Iyambae protected area kept fires at bay in 2024, a testament to Indigenous-led fire prevention investments

More

Elsewhere in Latin America, Primary Forest Loss Surged as Fires Raged

Many other countries in Latin America also saw large spikes in tree cover loss due to fire in 2024 fueled by widespread drought in the region. Fires caused at least 60% of the primary forest loss in Belize, Guatemala, Guyana and Mexico. These fires had devastating impacts on local communities, including hazardous air quality and loss of lives and homes. Increases in primary forest loss in Mexico and Nicaragua, driven in part by fires, vaulted them into the top 10 countries for tropical primary forest loss in 2024.

Agricultural expansion also drove primary forest loss across the region.

Many Latin American counties saw record high primary forest loss in 2024, largely due to fires

More

- Guatemala lost 2.7% of its primary forest in 2024, with widespread fires leading the president to issue a natural disaster declaration. In the north of the country, illegal cattle ranching and the expansion of informal settlements — sometimes with ties to organized crime — fueled forest loss, including in the Sierra del Lacandón National Park.

- Mexico’s tropical primary forest loss nearly doubled between 2023 and 2024, mostly from fires. Mexico’s National Forestry Commission, CONAFOR, reported over 8,000 fires and the largest burned area on record. Commercial agriculture, including cattle and soy, are also replacing primary forests. Half of Mexico’s primary forest loss in 2024 occurred in Campeche and Quintana Roo, where the presence of Mennonites — who have established intensive monoculture farming systems — has been growing.

- Nicaragua had the highest percentage of primary forest loss of any country in 2024, at 4.7%. Large fires spread throughout protected areas and Indigenous territories on the Caribbean coast, likely linked to agricultural expansion. Nearly 78% of the loss occurred in the Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, which lost 74,000 hectares of primary forest, 40% of which was due to fires. Indigenous territories have been threatened by deforestation from encroaching cattle ranches, mining and logging, often accompanied by violence. While agriculture is the main driver of primary forest loss, expansion of mining is occurring in some regions.

- Peru experienced a 135% increase in tropical primary forest loss due to fire between 2023 and 2024. Burning to clear land for agriculture was a major cause. The Office of the Ombudsman argued that recent modifications to the forest law played a role, as it exempts private land owners from requiring analyses and authorization before changing the land use of their properties, legitimizing prior illegal forest clearing for agriculture and facilitating further illegal deforestation.

- Guyana, a country that historically has had relatively low rates of primary forest loss, experienced a four-fold increase in tropical primary forest loss between 2023 and 2024, 60% of it from fire. Illegal and unregulated mining also plays an outsized role in driving forest loss, encroaching into Indigenous territories and leading to a rise in malaria cases. Mining was responsible for nearly 35% of primary forest loss in Guyana over the past 24 years. These losses come despite Guyana’s move to monetize its status as a “High Forest Low Deforestation” (HFLD) country to generate revenue through forest conservation.

Hotspots show areas in Latin America that were newly affected by fires in 2024

More

Colombia Returns to Higher Rates of Primary Forest Loss After a Dip in 2023

Primary forest loss jumped almost 50% in Colombia between 2023 and 2024.

Colombia primary forest loss increased in 2024 after falling in 2023

More

Unlike many other countries in Latin America, fires were not a major driver. The change in government in 2022 and its focus on forest conservation led to a large drop in primary tropical forest loss in 2023. Since then, challenges such as the presence of illegal groups and the resettlement of previously landless communities have led to more instability in remote areas, and may have contributed to the rise in forest loss.

Suspension of peace talks and an increase in violence in remote areas have also increased illegal mining and coca production and spurred forest loss, impacting Indigenous communities in particular. Elsewhere in Colombia, the conversion of forests for cattle production and oil palm plantations remain major drivers of primary forest loss.

For forest loss to drop again, the government must maintain the peace deal and develop deforestation-free livelihoods for local communities.

More

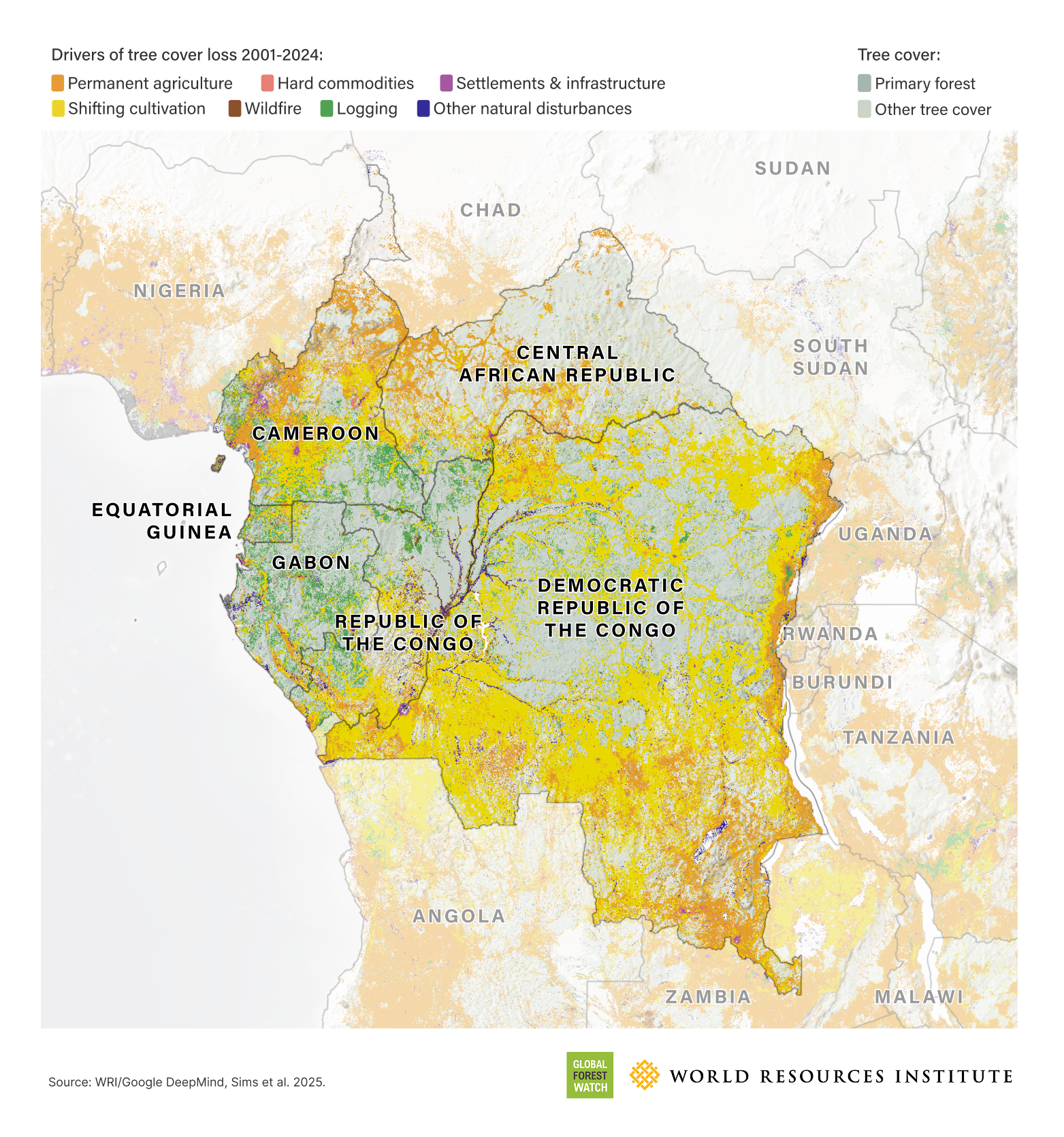

Smallholder Agriculture, Charcoal Production and Logging Drive Primary Forest Loss in the Congo Basin

Loss of the Congo Basin's expansive tropical primary forest continued in 2024, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the Republic of the Congo having their highest loss on record.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo both saw their highest primary forest loss on record in 2024

More

Causes of forest loss in the region include fires, removal of timber to make charcoal (the dominant form of energy), forest clearing for smallholder agriculture and shifting cultivation — a traditional form of subsistence farming where forests are cleared for temporary planting and then left fallow for a period while forests regrow. However, as cash crops are introduced in some parts of the Congo Basin, the scale of clearing is increasing and fallow periods are shorter. In these regions, forests are not regrowing, and the cultivation is becoming more permanent.

Shifting cultivation is the main driver of forest loss in the Congo Basin

More

Solutions to these drivers are challenging as many communities do not have alternative resources. DRC is one of the five poorest nations in the world, with many people relying on the forest for food and energy. With rising populations, this pressure on forests and their resources is unlikely to decrease.

Another factor in DRC is that people displaced by ongoing conflicts are forced to clear land for their survival. The conflict in DRC involving rebel groups who vie for control of the country’s vast natural resources has also led to many towns and industries in the eastern part of the country being taken by rebels. This includes charcoal supply chains and mines, creating instability and displacement that drive up forest loss.

In the Republic of the Congo, a “High Forest, Low Deforestation” (HFLD) country, loss in primary forests increased 150% from 2023 to 2024, almost double the amount of any previous year on record. Fires were responsible for 45% of the loss due to conditions that were drier and hotter than usual.

Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Central African Republic (CAR) have managed to keep forest loss stable overall, even amid a major political change in Gabon and relentless conflicts in CAR. Meanwhile Cameroon, like DRC and the Republic of the Congo, has seen an overall uptick in forest loss in recent years.

Gabon, Central African Republic and Equatorial Guinea saw stable forest loss in recent years

More

With many forest loss drivers linked to local livelihoods or displaced people, we need a more transformative approach that allows communities to lead forest protection efforts while placing community wellbeing in the center of all forest programs. Efforts to protect forests in the region should harness the full potential for countries and communities to receive payments for ecosystem services for the protection of forests, including through the generation of high integrity carbon credits.

In DRC, the Kivu-Kinshasa Green Corridor presents an opportunity to protect over 540,000 square kilometers of forest while promoting sustainable economic development for the 31 million people who live there. However, this area saw large amounts of forest loss in 2024. Ensuring these green projects remain a priority when DRC is experiencing conflict will be a challenge.

More

Primary Forest Loss Declines in Indonesia

Indonesia experienced an 11% decrease in primary forest loss from 2023 to 2024. Fires were mild and loss remained well below its mid-2010s peak.

Indonesia primary forest loss decreased in 2024, largely due to forest protection and fire management efforts

More

UMD's primary forest definition is different to Indonesia's legally defined primary forest area. Much of UMD’s primary forest loss in Indonesia is within areas that Indonesia classifies as secondary forest and other land cover. Learn more here.

More

2024 was the last year of President Joko Widodo’s administration, which prioritized forest protection, restoration and fire suppression. These efforts, along with late season rains and fire prevention from local communities and agribusinesses, helped keep fire rates low despite drought conditions in many places. Private sector efforts to reduce deforestation linked to commodities also contributed.

Most of the primary forest loss took place in areas adjacent to existing timber/wood fiber and oil palm plantations, small-scale agriculture, and mining areas, or was due to the expansion of logging. Rates of loss were up slightly in several provinces, including in Sumatera (Aceh, Bengkulu and South Sumatera) and Papua. Primary forest loss encroached into some protected areas, including continued losses in Kerinci Seblat, Tesso Nilo and the Leuser ecosystem on the island of Sumatra.

More

Primary Forest Loss Drops Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, but Challenges Persist

Primary forest loss also declined in many other countries in Southeast Asia. For example, Malaysia experienced a 13% reduction in primary forest loss compared to 2023, dropping out of the top 10 list for the first time. While this continued low rate is good news, Malaysia has lost nearly a fifth of its primary forest since the year 2001 and nearly a third since the 1970s. Government efforts to cap plantation areas and toughen forest laws are now working alongside corporate commitments to reduce deforestation.

Despite a 15% decrease in primary forest loss in Laos in 2024, total loss was still the second highest on record. Primary forest loss in Laos is mostly driven by agricultural expansion, fueled in part by investment from China, the largest importer of the country’s agricultural products. Laos’ poor economic situation may also be contributing as the increased cost of basic needs have pushed farmers to carve new agricultural plots from forests.

More

Fires Also Drive High Rates of Tree Cover Loss Outside the Tropics

Global tree cover loss was the highest on record in 2024,* increasing by 5% compared to 2023 to reach 30 million hectares. 2024 was the first time that major fires raged across both the tropics and boreal forests since our record-keeping began, resulting in 4.1 Gt greenhouse gas emissions due to fires across the globe, equivalent to more than 4 times the emissions from air travel in 2023.

Outside the tropics, fires drove most of the tree cover loss increase and were especially notable in Canada and Russia.

Outside the tropics, Canada and Russia saw high tree cover loss driven by fires in 2024

More

While fires are part of the natural forest dynamics in boreal regions and tree cover loss from these fires is typically temporary, fires have been larger, more intense and longer lasting in recent years. Research shows boreal forests are increasingly susceptible to drought and fires due to climate change, creating a feedback loop of worsening fires and carbon emissions.

While Canada did not see quite as much devastation in 2024 as its record-breaking 2023 fire season, it experienced double the amount of fire-driven loss than in previous years. Fires occurred mostly in Western Canada.

Russia experienced a large increase in tree cover loss in 2024, almost entirely due to fires in Eastern Siberia. Hotter, drier weather related to climate change has led to fire-prone conditions, drier peatlands and melted permafrost. Siberia’s vast peatland — the largest in the world — stores massive amounts of carbon that is released into the atmosphere when peat dries up and is burned.

More

2024 Is a Wake-up Call

We cannot afford to ignore the 2024 wake-up call. To halt and reverse forest loss by 2030, annual forest loss will need to fall by 20% each year from 2024 levels. It will take action across many fronts to get trends moving in the right direction:

- Sustained political leadership: Consistent declines in forest loss at the scale needed to reach 2030 goals are difficult to achieve. Progress is often tied to changes in political leadership, with gains easily reversed when priorities shift. To succeed, countries need long-term, cross-administration commitments backed by strong institutions and stable policies so that forest protection outlasts election cycles and political agendas. Signatories to forest commitments must also be held accountable by tracking progress toward the goals with transparent data and clear interim milestones.

- Decoupling commodity production from forest loss: Land is finite. As the global population reaches 8.5 billion by 2030, demand for food, energy, housing and infrastructure will increase. This puts growing pressure on land, including forests. Companies in forest-risk commodity sectors must accelerate progress towards their own and sector-wide deforestation-free supply chain targets. Regulators in producer and market countries must underpin these efforts by enforcing forest protection laws and requiring companies to ensure they are not sourcing commodities from recently deforested land. For example, the EU Deforestation Regulation, set to come into operation in 2026, restricts the import of select commodities produced on land deforested after 2020.

- Strong fire prevention and response: The hot and dry conditions that lead to fires are likely to worsen. Investment in fire prevention, early warning systems, rapid response equipment, enforcement measures, education on fire-free preparation of agricultural land, and prescribed burns to reduce flammability are needed to combat future fires.

- Combating nature crime: Illegal logging, mining and agricultural conversion associated with land grabbing are major drivers of forest loss. Stronger legal frameworks and enforcement, reducing corruption, empowering civil society groups and deploying innovative technologies to detect and deter crime are all critical to tackling it.

- More finance for forest protection and restoration: As part of broader efforts to close the financing gaps for climate and nature, this can include: reducing subsidies and investments that drive deforestation; increasing the flow of funding under existing forest pledges such as the Global Forest Finance Pledge, Congo Basin Pledge, and Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Forest Tenure Pledge; innovative instruments such as the proposed Tropical Forest Finance Facility, which aims to raise $250 billion to be drawn upon by tropical countries that meet thresholds for limiting deforestation; greater corporate use of high integrity forest-based carbon credits to supplement, not reduce, the pace of emissions reductions within a corporation’s own value chain; and debt-for-nature swaps for countries undertaking forest conservation initiatives.

- Advancing community-led forest economies: These are viable economies intrinsically linked to forest conservation and restoration, involving enterprises that are managed by (and benefit) Indigenous Peoples and local communities. They enable sustained socioeconomic development within and around standing forests — as an alternative to business-as-usual economic activities that are highly extractive or rely on converting forests to farms. Such economies are established through capacity-building, sector development, financing and coherent enabling policies. For example, the Pan-Amazon Network for Bioeconomy is focused on creating a forest economy that prioritizes the conservation of standing forests and the well-being of its local population.

- Aligning efforts to reduce deforestation with Biodiversity Framework goals: Target 3 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework aims to conserve 30% of land by 2030. However, much primary forest lies outside protected areas, so ensuring that these are within the conservation areas designated under this Target will support efforts to halt deforestation as well as supporting biodiversity goals.

Ultimately, progress will require locally tailored solutions, greater political will from both forested countries and those that import commodities from them, and adaptation to growing climate change risks. Without this range of solutions, forests — and the many benefits they provide — will continue to disappear.

*For global tree cover loss in all tree canopy density levels. For tree cover over 30% canopy density, 2016 and 2024 had very similar levels, both totaling 30 million hectares of loss.

Explore the data yourself on Global Forest Watch

More

{"Glossary":{"141":{"name":"agroforestry","description":"A diversified set of agricultural or agropastoral production systems that integrate trees in the agricultural landscape.\r\n"},"101":{"name":"albedo","description":"The ability of surfaces to reflect sunlight.\u0026nbsp;Light-colored surfaces return a large part of the sunrays back to the atmosphere (high albedo). Dark surfaces absorb the rays from the sun (low albedo).\r\n"},"94":{"name":"biodiversity intactness","description":"The proportion and abundance of a location\u0027s original forest community (number of species and individuals) that remain.\u0026nbsp;\r\n"},"95":{"name":"biodiversity significance","description":"The importance of an area for the persistence of forest-dependent species based on range rarity.\r\n"},"142":{"name":"boundary plantings","description":"Trees planted along boundaries or property lines to mark them well.\r\n"},"98":{"name":"carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e)","description":"Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) is a measure used to aggregate emissions from various greenhouse gases (GHGs) on the basis of their 100-year global warming potentials by equating non-CO2 GHGs to the equivalent amount of CO2.\r\n"},"153":{"name":"climate domain","description":"Major ecosystem regions, summarized as boreal, temperate, tropical and subtropical.\u0026nbsp;"},"99":{"name":"CO2e","description":"Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) is a measure used to aggregate emissions from various greenhouse gases (GHGs) on the basis of their 100-year global warming potentials by equating non-CO2 GHGs to the equivalent amount of CO2.\r\n"},"1":{"name":"deforestation","description":"The change from forest to another land cover or land use, such as forest to plantation or forest to urban area.\r\n"},"77":{"name":"deforested","description":"The change from forest to another land cover or land use, such as forest to plantation or forest to urban area.\r\n"},"76":{"name":"degradation","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes.\r\n"},"75":{"name":"degraded","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes.\r\n"},"79":{"name":"disturbances","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"68":{"name":"disturbed","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"65":{"name":"driver of tree cover loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"70":{"name":"drivers of loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"81":{"name":"drivers of tree cover loss","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation)."},"102":{"name":"evapotranspiration","description":"When solar energy hitting a forest converts liquid water into water vapor (carrying energy as latent heat) through evaporation and transpiration.\r\n"},"154":{"name":"fastwood monoculture","description":"Stands of single species planted trees that grow quickly.\u0026nbsp;"},"53":{"name":"forest degradation","description":"The reduction in a forest\u2019s quality and ability to perform ecosystem services, such as carbon storage and water regulation, due to natural and anthropogenic changes."},"54":{"name":"forest disturbance","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"100":{"name":"forest disturbances","description":"A discrete event that changes the structure of a forest ecosystem.\r\n"},"5":{"name":"forest fragmentation","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"155":{"name":"Forest Landscape Restoration","description":"The ongoing process of restoring landscapes to regain ecological functionality and enhance human well-being across deforested or degraded forest landscapes."},"156":{"name":"forest moratorium","description":"A temporary restriction on activities that cause forest loss or degradation."},"69":{"name":"fragmentation","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"80":{"name":"fragmented","description":"The breaking of large, contiguous forests into smaller pieces, with other land cover types interspersed.\r\n"},"74":{"name":"gain","description":"The establishment of tree canopy in an area that previously had no tree cover. Tree cover gain may indicate a number of potential activities, including natural forest growth or the crop rotation cycle of tree plantations.\r\n"},"143":{"name":"global land squeeze","description":"Pressure on finite land resources to produce food, feed and fuel for a growing human population while also sustaining biodiversity and providing ecosystem services.\r\n"},"7":{"name":"hectare","description":"One hectare equals 100 square meters, 2.47 acres, or 0.01 square kilometers.\r\n"},"66":{"name":"hectares","description":"One hectare equals 100 square meters, 2.47 acres, or 0.01 square kilometers."},"67":{"name":"intact","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"78":{"name":"intact forest","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"8":{"name":"intact forests","description":"A forest that contains no signs of human activity or habitat fragmentation as determined by remote sensing images and is large enough to maintain all native biological biodiversity.\r\n"},"55":{"name":"land and environmental defenders","description":"People who peacefully promote and protect rights related to land and\/or the environment.\r\n"},"161":{"name":"logging concession","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"157":{"name":"logging concessions","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"160":{"name":"Logging concessions","description":"A legal agreement allowing an entity the right to manage a public forest for production purposes, including for timber and other wood products."},"9":{"name":"loss driver","description":"The cause of tree cover loss, such as agriculture or urban development. There are direct drivers, which are the immediate cause of the loss, and indirect drivers, which are the secondary cause of loss (i.e., land speculation).\r\n"},"10":{"name":"low tree canopy density","description":"Less than 30 percent tree canopy density.\r\n"},"104":{"name":"managed natural forests","description":"Naturally regenerated forests with signs of management, including logging and clear cuts.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"91":{"name":"megacities","description":"A city with more than 10 million people.\r\n"},"57":{"name":"megacity","description":"A city with more than 10 million people."},"86":{"name":"natural","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions).\u0026nbsp;"},"12":{"name":"natural forest","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions). \r\n"},"63":{"name":"natural forests","description":"A forest that that grows with limited or no human intervention. Natural forests can be managed or unmanaged (see separate definitions).\u0026nbsp;"},"144":{"name":"open canopy systems","description":"Individual tree crowns that do not overlap to form a continuous canopy layer.\r\n"},"88":{"name":"planted","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"14":{"name":"planted forest","description":"Planted trees \u2014 other than tree crops \u2014 grown for wood and wood fiber production or for ecosystem protection against wind and\/or soil erosion.\r\n"},"73":{"name":"planted forests","description":"Planted trees \u2014 other than tree crops \u2014 grown for wood and wood fiber production or for ecosystem protection against wind and\/or soil erosion."},"148":{"name":"planted trees","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"149":{"name":"Planted trees","description":"Stands of trees established through planting, including both planted forest and tree crops."},"15":{"name":"primary forest","description":"Old-growth forests that are typically high in carbon stock and rich in biodiversity. The GFR uses a humid tropical primary rainforest data set, representing forests in the humid tropics that have not been cleared in recent years.\r\n"},"64":{"name":"primary forests","description":"Old-growth forests that are typically high in carbon stock and rich in biodiversity. The GFR uses a humid tropical primary rainforest data set, representing forests in the humid tropics that have not been cleared in recent years.\r\n"},"58":{"name":"production forest","description":"A forest where the primary management objective is to produce timber, pulp, fuelwood, and\/or nonwood forest products."},"89":{"name":"production forests","description":"A forest where the primary management objective is to produce timber, pulp, fuelwood, and\/or nonwood forest products.\r\n"},"159":{"name":"restoration","description":"Interventions that aim to improve ecological functionality and enhance human well-being in degraded landscapes. Landscapes may be forested or non-forested."},"87":{"name":"seminatural","description":"Forest with predominantly native trees that have not been planted. Trees are established through silvicultural practices, including natural regeneration or selective thinning.FAO"},"59":{"name":"seminatural forests","description":"Forest with predominantly native trees that have not been planted. Trees are established through silvicultural practices, including natural regeneration or selective thinning.FAO"},"96":{"name":"shifting agriculture","description":"Agricultural practices where forests are cleared, used for agricultural production for a few years, and then temporarily abandoned to allow trees to regrow and soil to recover.\u0026nbsp;"},"103":{"name":"surface roughness","description":"Surface roughness of forests creates\u0026nbsp;turbulence that slows near-surface winds and cools the land as it lifts heat from low-albedo leaves and moisture from evapotranspiration high into the atmosphere and slows otherwise-drying winds. \r\n"},"17":{"name":"tree cover","description":"All vegetation greater than five meters in height and may take the form of natural forests or plantations across a range of canopy densities. Unless otherwise specified, the GFR uses greater than 30 percent tree canopy density for calculations.\r\n"},"71":{"name":"tree cover canopy density is low","description":"The percent of ground area covered by the leafy tops of trees. tree cover: All vegetation greater than five meters in height and may take the form of natural forests or plantations across a range of canopy densities. Unless otherwise specified, the GFR uses greater than 30 percent tree canopy density for calculations.\u0026nbsp;\u0026nbsp;"},"60":{"name":"tree cover gain","description":"The establishment of tree canopy in an area that previously had no tree cover. Tree cover gain may indicate a number of potential activities, including natural forest growth or the crop rotation cycle of tree plantations.\u0026nbsp;As such, tree cover gain does not equate to restoration.\r\n"},"18":{"name":"tree cover loss","description":"The removal or mortality of tree cover, which can be due to a variety of factors, including mechanical harvesting, fire, disease, or storm damage. As such, loss does not equate to deforestation.\r\n"},"163":{"name":"tree cover loss due to fire","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"164":{"name":"tree cover loss due to fires","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"162":{"name":"tree cover loss from fires","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"},"150":{"name":"tree crops","description":"Stand of perennial trees that produce agricultural products, such as rubber, oil palm, coffee, coconut, cocoa and orchards."},"85":{"name":"trees outside forests","description":"Trees found in urban areas, alongside roads, or within agricultural land\u0026nbsp;are often referred to as Trees Outside Forests (TOF).\u202f\r\n"},"151":{"name":"unmanaged","description":"A forest that grows without human intervention and has no signs of management, including primary forest.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"105":{"name":"unmanaged natural forests","description":"A forest that grows without human intervention and has no signs of management, including primary forest.Lesiv et al. 2022, https:\/\/doi.org\/10.1038\/s41597-022-01332-3"},"158":{"name":"tree cover loss from fire","description":"The mortality of tree cover where forest fires were the direct cause of loss.\u0026nbsp;"}}}

.png)

.png)

.png)